In every photograph time is evident in two ways, one is shutter speed, but much more importantly, every photograph must show the effect of never ending time itself on the scene. That is what we are going to examine now: how time influences and is represented in various ways in still photography.

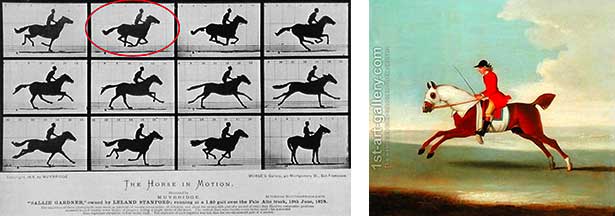

From the earliest days of photography, the instantaneity of photography was appreciated as a way to “see the unseen moment”. Perhaps the most famous early example of this is Muybridge’s time lapse photographs of a running horse, which, among other things, proved once and for all that all four legs do, in fact, leave the ground at the same time, tucked under the horse , something that was previously believed to be impossible.

Time-lapse photos showing accurate movement versus painting of a running horse showing incorrect placement of the horse’s legs.

This approach, although the photographs are combined in a much more sophisticated way, is still in use, as we can see in the surfing photographs of Blair Seagram, where movement through the waves is shown by placing the same surfer at several different positions in the same photograph to show his trajectory through the water. The image is created from several photographs by stitching them together in Photoshop. There are many other techniques that photographers use to indicate motion. One of the earliest techniques, which is still in use today, is the use of panning. That is to say to follow the trajectory of the moving object, say a racing car, with the camera. The result is that the background is rendered with “motion blur” and the object is much sharper, thus imparting the feeling of speed, producing a fairly accurate analogue of the way the human eye sees a fast moving object, concentrating on the object, and nothing else. Early examples of this technique often were made with large format cameras and relatively slow moving focal plan shutters, which as they moved a slit from the top of the frame to the bottom, created a forward diagonal to the image, which greatly increased the impression of speed, even though this image did not correspond to any thing seen by the human eye. This look was then adopted by illustrators to show speed, even if the background was no longer blurred.

There are many other techniques that photographers use to indicate motion. One of the earliest techniques, which is still in use today, is the use of panning. That is to say to follow the trajectory of the moving object, say a racing car, with the camera. The result is that the background is rendered with “motion blur” and the object is much sharper, thus imparting the feeling of speed, producing a fairly accurate analogue of the way the human eye sees a fast moving object, concentrating on the object, and nothing else. Early examples of this technique often were made with large format cameras and relatively slow moving focal plan shutters, which as they moved a slit from the top of the frame to the bottom, created a forward diagonal to the image, which greatly increased the impression of speed, even though this image did not correspond to any thing seen by the human eye. This look was then adopted by illustrators to show speed, even if the background was no longer blurred. As the technical elements of action photography continued their relentless development, several factors made it possible to actually stop action and eliminate the need to pan the camera. These were increased film speeds, faster lenses, faster and smaller focal plane shutters, and high power strobes that enabled exposures as fast as a eight thousandths of a second. This perfectly stopped action became to imply action, even though there is no apparent movement.

As the technical elements of action photography continued their relentless development, several factors made it possible to actually stop action and eliminate the need to pan the camera. These were increased film speeds, faster lenses, faster and smaller focal plane shutters, and high power strobes that enabled exposures as fast as a eight thousandths of a second. This perfectly stopped action became to imply action, even though there is no apparent movement. The photo might be said to show the artifacts of action such as a boiling wake left behind a sail boat frozen in time, tells us how fast the boat was moving when the shot was taken, or the ball player shown frozen in mid air, even thoug we can not really see him like that.In fact, we are susceptible to the artifacts of speed in real life: who among us has not believed that our train was starting to leave the station, when in reality we were simply fooled by the train on the next platform, that had started to move instead of us.

The photo might be said to show the artifacts of action such as a boiling wake left behind a sail boat frozen in time, tells us how fast the boat was moving when the shot was taken, or the ball player shown frozen in mid air, even thoug we can not really see him like that.In fact, we are susceptible to the artifacts of speed in real life: who among us has not believed that our train was starting to leave the station, when in reality we were simply fooled by the train on the next platform, that had started to move instead of us.

Another type of motion blur is axial motion blur which is created by pointing a moving camera in the direction of motion, instead a fixed camera moving across the picture plan, it to give the feeling of motion. This effect can also be created by zooming the lens rapidly while using a slow shutter speed. Perhaps no form of photography is more related to classical painting than portraiture. Painted portraits almost invariably show the subject, the sitter as they are known, in repose. Obviously this facilitated the process of the painting which could be quite protracted. It is said that Ingres’s portrait of Madame Moitessier, finished in 1858, was actually begun in 1844! Despite the fact that a modern portrait takes a mere fraction of a second, the sitter is almost always shown in repose. One wonders if this is simply following tradition, or if the face in repose is more revealing, or if some other factor is at play.

Perhaps no form of photography is more related to classical painting than portraiture. Painted portraits almost invariably show the subject, the sitter as they are known, in repose. Obviously this facilitated the process of the painting which could be quite protracted. It is said that Ingres’s portrait of Madame Moitessier, finished in 1858, was actually begun in 1844! Despite the fact that a modern portrait takes a mere fraction of a second, the sitter is almost always shown in repose. One wonders if this is simply following tradition, or if the face in repose is more revealing, or if some other factor is at play.

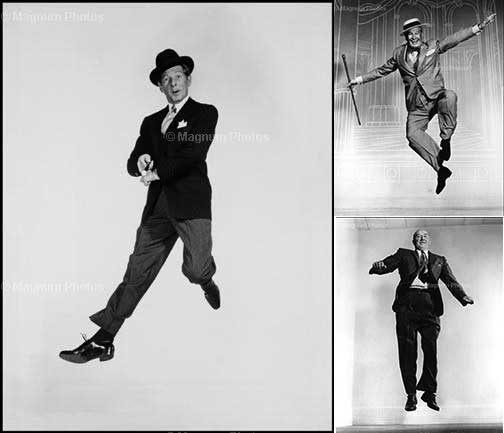

On the other hand, the advent of faster camera did lead to experiments in what might be called portraits in motion. In fact, Phillipe Halsman developed the technique of “jump shots” in which the sitter becomes a jumper. He observed: “When you ask a person to jump, his attention is mostly directed toward the act of jumping and the mask falls so that the real person appears. This proved to be much more accurate in the case of real dancers like Danny Kaye or Maurice Chavlier, and much less so in the case of the president of US Steel. Are we surprised? Another way of interpreting the passage of time was to use an extremely long, or extremely short exposure to either show the effect of a long passage of time, or at the opposite end of the spectrum, an incredible short instant, as in this high speed shot of a drop of water, shows once again an instant in time invisible to the naked eye.

Another way of interpreting the passage of time was to use an extremely long, or extremely short exposure to either show the effect of a long passage of time, or at the opposite end of the spectrum, an incredible short instant, as in this high speed shot of a drop of water, shows once again an instant in time invisible to the naked eye. For February’s exercise, we are going to consider the matter of illustrating motion, or stillness, and members are requested to bring in some photographs that illustrate an appropriate technique, or perhaps several techniques on the same subject in an effort to explore which might be the most effective.

For February’s exercise, we are going to consider the matter of illustrating motion, or stillness, and members are requested to bring in some photographs that illustrate an appropriate technique, or perhaps several techniques on the same subject in an effort to explore which might be the most effective.

Finally we will close with this very interesting exposure of the Toronto skyline which took a entire year to expose, with a camera with a very small pinhole for a lens. The lens was left open all year, and the film, actually paper, was exposed to so much light, it was not developed, but scanned, which erased the image, but not before the scan was complete. This compelling image shows that for the inventive and creative photographer, there is always the possibility of creating original and fascinating way to illustrate the passage of time in a single static frame.